Karl Friston — Functioning Brains and Psychotic Societies

On the Free Energy Principle, societal boundaries, cancer, and the beauty of sparsity.

“There’s a popular view that connectivity, in the Facebook sense, is a good thing. In my world, it’s really bad. Dense connectivity is the killer. It is death.” — Karl Friston

I would readily infer that Karl Friston will be remembered as one of the most important scientific figures of the 21st century.

He is widely considered the most influential neuroscientist alive, not least for inventing the statistical techniques that nearly every brain imaging researcher uses daily. As a former psychiatrist, he has also made important contributions to our understanding of psychopathologies like schizophrenia and depression.

What is truly remarkable is that through his understanding of the human mind, Friston may have discovered one of the deepest principles of nature, which he calls the Free Energy Principle (FEP). Alongside its applied corollary, active inference, the FEP was originally presented as a physics-based theory of the brain and human behavior, but it has since been expanded to explain the fundamental dynamics of everything from living organisms to elementary particles.

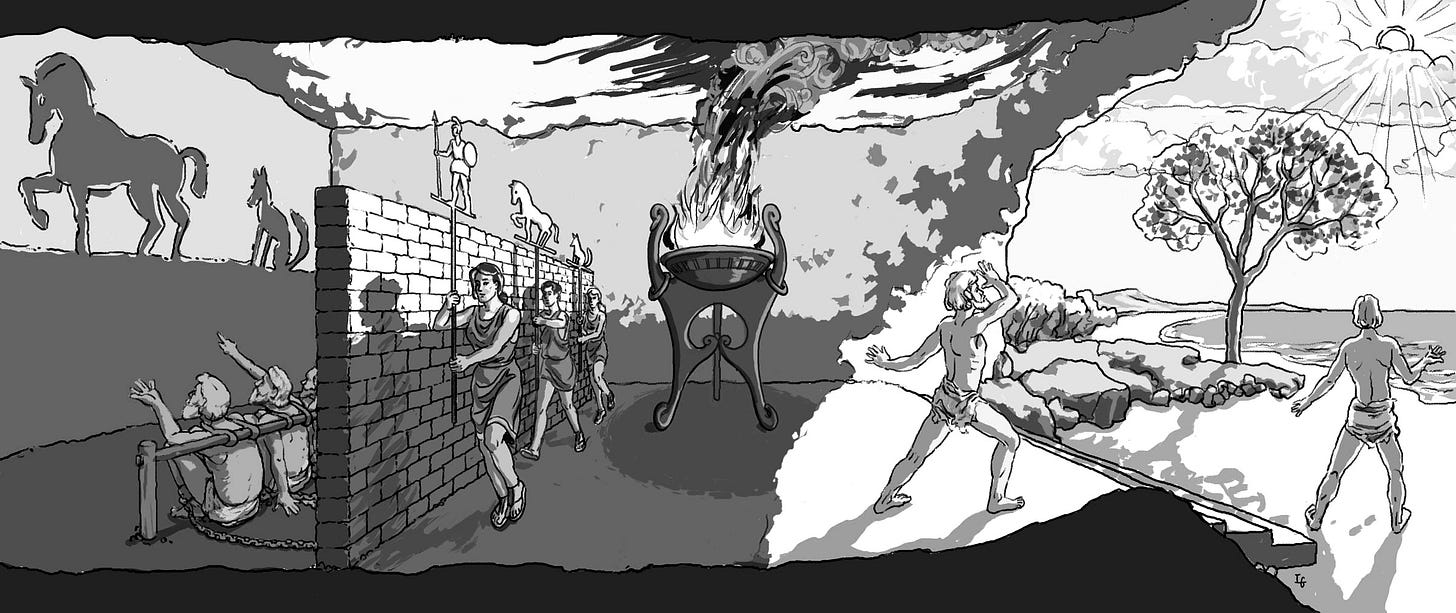

At its heart, the Free Energy Principle is remarkably elegant and simple, but it is considered notoriously difficult to wrap your head around upon first reading. The easiest way is to begin with your own mind. As Plato intuited in his allegory of the cave, we humans do not see the world or its causes directly, as if through a window. Rather, we are trapped within the confines of our own minds, receiving information about the world indirectly through the senses.

Plato illustrates our condition by imagining humanity as chained inside a cave and presented with shadows on the wall reflected by a fire. His point is that we never experience reality as it really is, only its shadowy reflection. The work of the philosopher (and the scientist) is to look past the shadows, to discover the truth lurking behind them; perhaps even escape the cave entirely.

In this way, our brain is designed to interpret the information it receives from the sensorium so that we can survive and make sense of the world. According to the FEP, the brain is constantly attempting to minimise free energy, which means reducing the error between our model of the world and what our senses are telling us about it. Whenever the brain encounters a prediction error, it either updates its model to better reflect sensory evidence or acts on the world to make its predictions come true. Perceptual illusions and delusional beliefs are all a reflection of how our brains can get this process wrong.

The beauty and explanatory power of the FEP come from the fact that its mathematical formulation readily applies to all the independent objects we find in the universe, whether they be brains or organisms, planets or particles. It has been taken up by physicists, biologists, computer scientists, and even economists. Because of its scale-free nature, it allows us to interpret all things as making inferences about their worlds, fighting the relentless march of entropy in order to persist through time for as long as possible. It means that at the most fundamental level, we humans have more in common with the rest of the universe than we might think. One implication of this is that physics and cognition are two sides of the same coin. It basically rejects the mind/matter dualism that has been so ingrained in our thinking since the time of Descartes, and thus encourages a very different way of conceptualizing our universe.

As the physicist Chris Fields has suggested, the Free Energy Principle and other contemporary developments in physics are inviting us to transcend traditional disciplinary and conceptual boundaries in science. Perhaps one day it will allow us to rigorously unify physics with biology, psychology, and even sociology.

It is this latter area to which I’d like to turn your attention. Societies, seen through the lens of the FEP, can be viewed as cognitive entities with dynamics that often mirror our own psychology. As such, it makes for an interesting window into what is, in my opinion, one of the most important scientific theories of our time.

With that in mind, please enjoy this dialogue with Karl Friston, where we discuss the Free Energy Principle and its application to societies.

The Organization Of Self And Society

GUNNAR: In the last few years working as a journalist, I’ve been driven to think more about the topic of governance and societies. Since I had become fascinated by the Free Energy Principle in university, I often have it in the back of my mind whenever I am learning something new. And so when I was thinking about societies, political institutions, and the like, I felt that the FEP might be a way to apply rigorous physics-based thinking to these topics. Since the FEP applies from the scale of organisms all the way down to brains, cells, molecules, atoms, etc, then it should, in principle, be equally useful to apply it all the way up to societies and ecosystems. It seems to allow you to ask the question: might a society operate on the same kind of dynamics that the FEP describes in the brain? But when I went looking around for answers on that in the scientific literature, I couldn’t find much on it. And so I was really curious to hear what you might think about that.

KARL FRISTON: As you say, I think that is an under-explored, or at least only provisionally explored, application of the Free Energy Principle. Fundamentally, the FEP is a method in physics. So it has to be applied. It’s a tool. And I think you’ve rightly identified the key thing here, and that is its scale invariance. The mathematical premise of the FEP means that the same principle should be operating at all scales, where you derive one scale from a coarse-graining of the scale below. And therefore, if it is apt to describe a neuron, it should also be apt to describe a neural network, and it should also be apt to describe a World Wide Web, or anything else that can be articulated as a random dynamical system or some coupled dynamical system. All these should yield to an application of the Free Energy Principle.

GUNNAR: Well, in that case, I’ve heard you explain the principle to lots of people in different fields. And you always say that you try to explain it from slightly different angles depending on who you’re talking to and what their expertise is. So I’m very curious to hear how you might tell the story of the FEP if you were aiming your explanation at someone trying to understand the structure and dynamics of a higher-scale system like a society?

KARL FRISTON: I think you’d probably start with the notion of self-organization, and just intuit that from the perspective of people like Alan Turing and the notion of Turing pattern formation, or from the perspective of modern-day theorists like Michael Levin and his ideas around distributed cognition or collective intelligence in cellular organisms. So you’re talking about an explicitly biomimetic self-organization that is both distributed and federated, and you’re trying to find the rules that underwrite the formation and the organization of multiple things operating together.

From there, you can start to identify the scale at which things exist. So ‘things’ could be people, or they could be communities, or they could be political in-groups. They could be countries. They could be ideologies or theistic fates. At an appropriate level, you can now search for the rules that apply to any pattern or self-organized set of things, any ensemble of things. Then ask yourself: How would you describe the dynamics and the evolution of these things from the point of view of physics? So I’d take a physics perspective on this, and this is where the Free Energy Principle would come in.

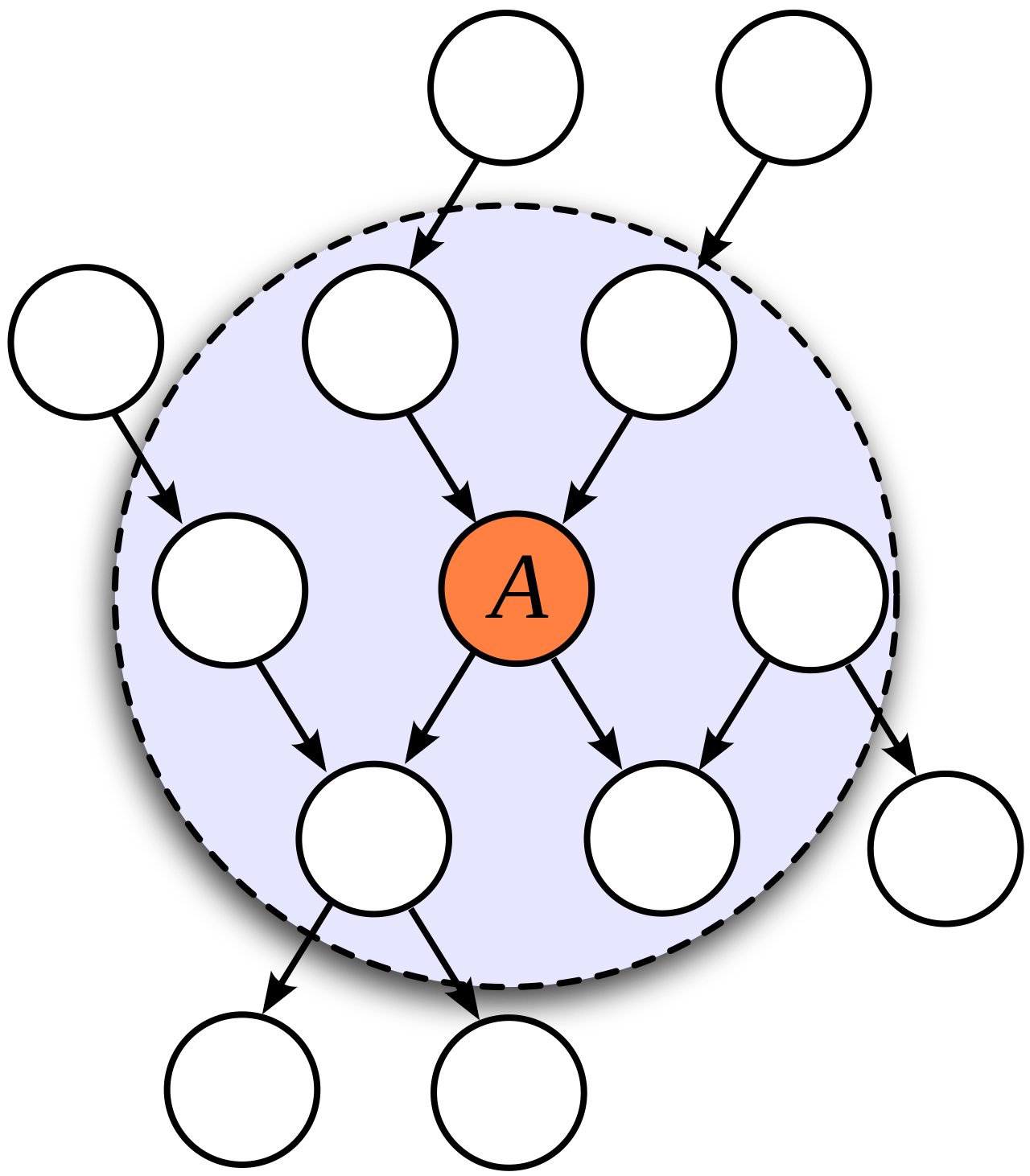

OK, I realize I’m sort of half trying to explain this to you, and half trying to explain how I would explain it to somebody else… so I’ll just explain it to me! First of all, you have to define what you are describing. And what you are describing is a kind of system that has a particular sustainability or persistence in time. We’re only interested in describing those structures that do not dissipate immediately. As soon as you do that, you have to define what you mean by a “structure” or “thing”. And that’s where you would introduce the notion of a Markov blanket. That’s going to be crucial for our conversation. So to talk about one thing in relation to, or in exchange with, another thing, you have to be able to individuate or demarcate that thing, or the states that constitute this thing from the other thing, and from everything else.

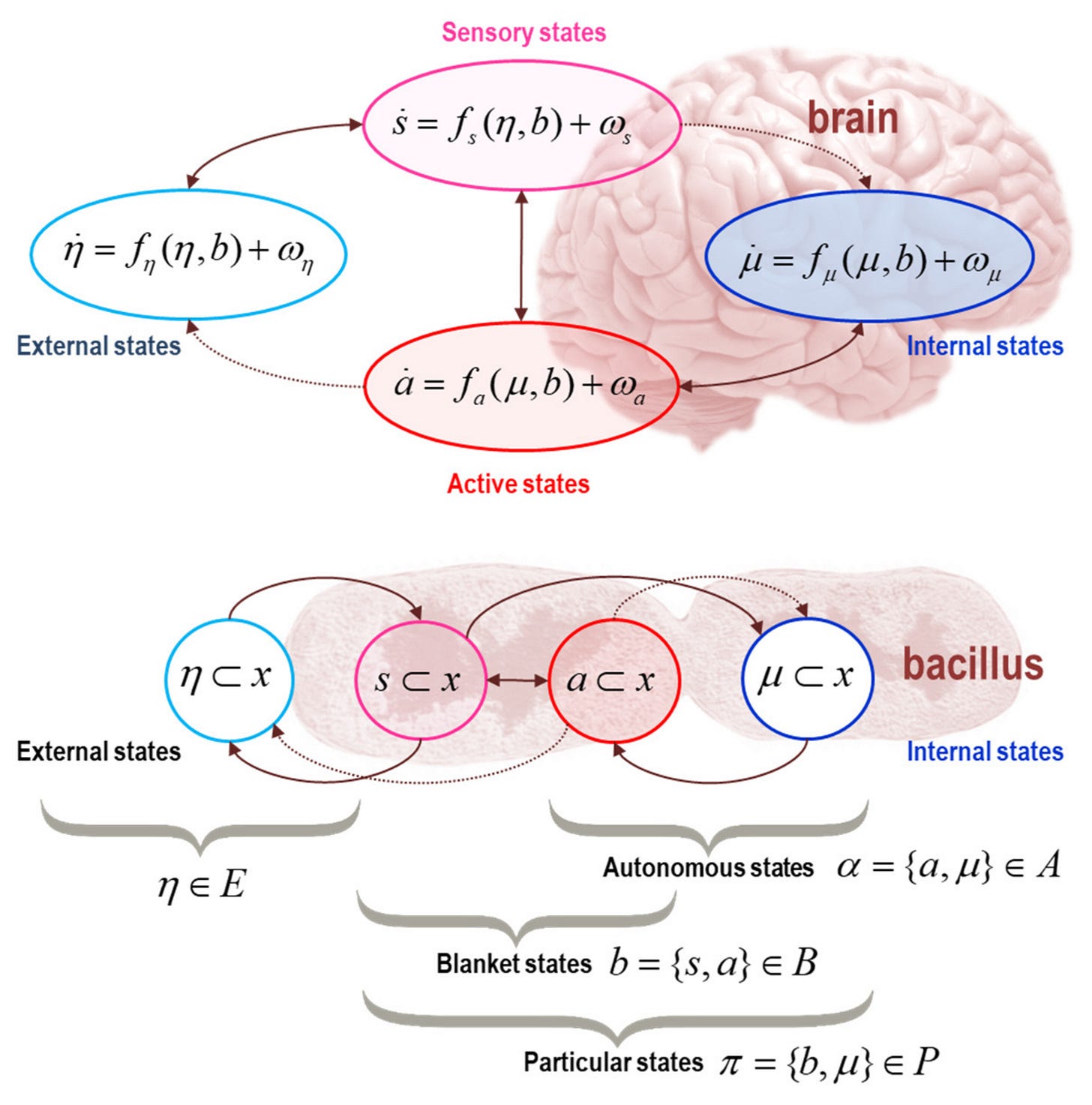

That brings to the table something peculiar to the Free Energy Principle, which you won’t find in either quantum physics or, in fact, statistical physics. And that’s because they always assume there’s a container, such as a heat bath in statistical physics, or a potential well in quantum physics. The Free Energy Principle goes beyond that. It asks: How does the heat bath or the potential well itself emerge? And that plays a crucial role in individuating the states of one thing, or the states that separate one thing from another thing. So what the free energy principle does is say: Any system that possesses a Markov blanket can now be read in terms of effectively modeling or making inferences about external states based on the information it has access to, which comes from the sensory sector of its Markov blanket.

Just to put a bit of flesh on that… If we were talking about a brain, then we’re talking about the sensory input or sensory states. It is the way the world impresses itself on my sensory epithelium: my eyes, my ears, my skin. If I were talking about an office, it would be anything that influences what’s going on inside the office building. So the receptionist, the postman delivering letters, basically anything that influences what’s happening on the inside. And then the other direction of travel would be the active states or the active sector of the Markov blanket. This would be anything on that boundary that influences the external states. So it would be, for example, any of my drivers transporting goods away from a factory, or anything that can be seen from the outside. In a society, it might be the journalists gathering information on the ground. For the government, it might be the intelligence services. It [the Markov blanket] is whatever part of the system that is gathering information or taking in resources from the outside, and exchanging information or trading goods to the outside.

And once you’ve got a partition of inside and outside, or internal and external states, you now have some system that is in open exchange with an environment, but only vicariously through boundary or blanket states. So that gives you a direction of travel both ways, where the inside influences the outside through active states, and the outside influences the inside through the sensory states.

You can then describe the dynamics of the internal states and the active states, namely the autonomous states, as effectively minimizing, or performing a gradient descent, on this free energy functional. How can you interpret this free energy functional? Well, you could adopt a number of different perspectives. You can interpret it as surprise or surprisal, or self-information. And what that means is that, just by existing in a sustainable way and maintaining my demarcation or my integrity in terms of my boundary, it will look as if I’m trying to act upon the world and make sense of the world through my sensory states in a way that’s minimizing surprise or prediction error. That would allow you to tell a predictive coding story.

Or you could say, well, this quantity, this variational free energy, is from a statistical perspective the negative of log evidence. That term sounds quite glorious, but you can just express that as self-evidencing. So what does that mean? Well, it basically means it will look as if I’m actively soliciting evidence for my own model and my own existence within this sort of ecosystem, or in the context of all these other things around me in my world. And you can also read that evidence as Bayesian model evidence, so it also looks as if you’ve got a Bayesian brain at some level in your institution or in your head. You can also read that as evidence accumulation. So all of these things—the ways that people talk about self-organization via information-theoretic or belief-updating terms—fall very neatly out of this fundamental property, which any system that has a Markov blanket must possess if and only if it exists for a non-trivial amount of time. Now all of this is probably a bit too technical for most people...

Boundaries In Flux

GUNNAR: I’m sure we can make it more manageable by digging into some of the specifics and asking how they might apply to what we’re talking about. Like you said, one of the most important concepts here is the Markov blanket, which allows us to describe a system as distinct from its environment, or from other systems that might surround it. Now, when you first hear about this idea of a Markov blanket, it naturally evokes an image of a literal physical sheet or skin that wraps around something, or blankets something. And that is quite easy to understand for things like, say, a cell. You can just think of a cell’s Markov blanket as the cell membrane. Same for a person, you can imagine that the Markov blanket is the person’s skin and everything you can see from the outside. But once you get into higher-scale systems that we are embedded in, the Markov blanket becomes a bit more intangible and hard to identify. Obviously, for nations, we have the idea of borders, but those borders are not always marked by literal physical barriers. There are many places where you could walk across a border without even realizing it, unless you were looking at a map.

KARL FRISTON: Yes, absolutely. Although it is true that you often can identify the Markov blanket by just looking for a literal boundary. Like you say, the obvious example for someone looking at geopolitical dynamics would be to consider what’s happening within and between national borders. To put it in system theory terms, a Markov blanket is just specifying a statistical boundary between systemic structures in terms of inputs and outputs. So you can just replace active states with outputs and sensory states with inputs, and all you’re doing is writing down a particular sparsity structure where you are defining how multiple systems engage with each other and self-organize through information exchange. So in the case of you and me, my input becomes your output, and my output becomes your input.

Mathematically, what that means is that because you’ve got this sparse exchange between entities, then if I know all the message passing between the two entities, I know everything that I need to know in order to predict how I’m going to change, personally, institutionally, structurally. I only need to know my inputs and outputs, and that’s it. So technically, this means that there’s a conditional statistical independence between the inside and the outside, given the transactions across the boundary.

Clearly, you can draw blankets at many different scales. You can have, not uncountable, but a very large number of blankets by partitioning things in different ways, and you can get blankets within blankets within blankets. So there’s not one blanket; it’s just that there is conditional independence at different levels. Some people call this D-separation in graph theory. It means that you can identify a set of internal states that are distinguished from some other states via their blanket states, but you can draw blankets in many different ways.

And it might be worthwhile just pointing out that Markov blankets are so ubiquitous that you couldn’t dispense with them if you wanted to talk about, say, hierarchies, such as organizational hierarchies or the hierarchical graphical structures in deep learning. A hierarchy is just a statement of the fact that you have got the kind of sparse coupling that affords a Markov blanket between the subordinate and the superordinate level. So as soon as you talk about hierarchies, you are implicitly inducing a particular kind of Markov blanket structure. You are suggesting blankets within blankets within blankets.

GUNNAR: I think that language actually offers a very interesting way of looking at countries and societies across time. Because, if you take a tertiary look at history, you’ll find that our current map of borders, or “Markov blankets,” is misleading if you project backwards in time. I had a history teacher in Kyoto make that point very explicitly, that if you go back into the history of Japan, you’ll find the feudal period when there may have been a nominal emperor, but there was not really anything you could call the “one nation of Japan”. Instead, the internal dynamics of Japan at that time were defined by a bunch of regional sub-domains with different rulers all warring with each other, so that the borders were constantly shifting, fluctuating in and out of existence, absorbing each other and splitting up again. It was only later that the country was unified in such a way that you might talk about Japan being one entity ruled from the top down, so to speak. So, you can imagine that there was once a collection of quite powerful entities with their own Markov blankets, but now there is a more unified, centralized entity, although there are still gradations within that.

KARL FRISTON: Absolutely, and you mentioned a key concept there, which is fluctuation. I think that’s quite an important insight that one gets when looking at the maths of this. It has been demonstrated with numerical experiments, looking at self-organization at different scales, that the fluctuation of the Markov blankets is faster the smaller they are. So if you’ve got the border of Japan, and then you’ve got lots of warring tribes within Japan, then you would predict that the internal borders amongst the warring tribes would come and go on a faster time scale than the larger border (fully acknowledging that even the larger border may fluctuate). And so to be clear, a society or a nation’s Markov blanket is not tied to a GPS location; it is just in the culture and in who’s talking to whom. It is defined by the actual input-output trading relationships, if you like, that unfold within the system.

So, as you say, there is an obvious kind of fluctuation in the skin-like notion of a Markov blanket. But that Markov blanket will contain multiple smaller Markov blankets, and crucially, they change faster or last for a shorter amount of time than the larger one. So we can imagine going all the way up to a notion of Gaia, the biosphere, which provides us with a very slowly fluctuating Markov blanket that contains the kind of blanket partitions that somebody looking at climate change or other long-term weather and geological components would identify, like the movement of oceanic plates. And then you’d have faster-changing things, such as geopolitical structures, right down to the changes that you probably experienced in your household with the arrival of babies and girlfriends.

In other words, there is this lawful ascension of temporal scales that you get when you think about Markov blankets. Just for your interest, and you’ll probably never say this again, but that structure inherits from something called the renormalization group in maths and physics, which is at the heart of the scale-invariance we were talking about before. So as you coarse-grain in terms of identifying Markov blankets at larger and larger scales of self-organization, not only do you encompass more space of a certain kind, but also more time. Therefore, Markov blankets that are bigger last longer, and Markov blankets that are smaller are usually more transient.

Sparsity, And Soups

GUNNAR: A term you’ve used a couple of times so far that I think is important is sparsity. I’ve heard you make the point elsewhere that one of the most aesthetically beautiful and functionally elegant aspects of the brain is its sparse connectivity. So, basically, despite the brain having billions of neurons, which form this holistic web out of trillions of connections, each neuron is actually only connected to a very small subset of the rest. Although we imagine the brain as one big bundle of connections, it really has this beautifully sparse structure where neurons are mostly connected to their neighbors, and these neighboring connections fan out in a very ordered manner into a broader structure that is hierarchically organized. And that is not necessarily an immediately intuitive idea, because people feel themselves to be of one mind, so to speak, so they imagine the brain to be more singularly unified in its connectivity. So why is sparsity such a good thing from the perspective of having a functional self-organizing structure?

KARL FRISTON: That’s an excellent question, which I think also would be really usefully unpacked in terms of notions of deglobalization. There’s a popular view that mass connectivity, in the Facebook sense, is a good thing. In my world, it’s really bad. Dense connectivity is the killer. It is death.

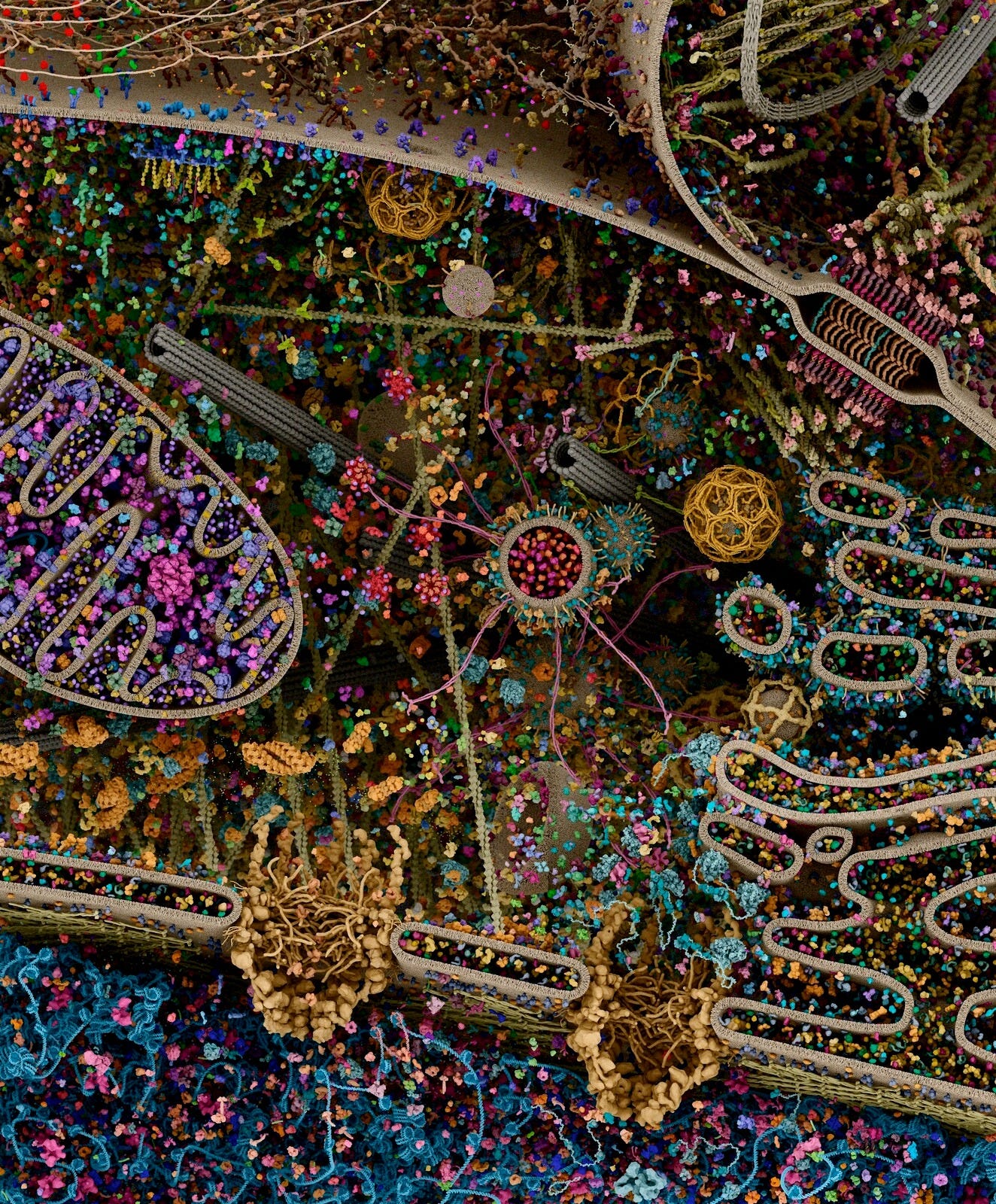

That is really just an inversion of the truism that for things to exist—by which I mean they persist in some characteristic space over time—you are explicitly saying that their Markov blanket persists. But we’ve just said the Markov blanket is defined in terms of sparse coupling; it’s defined in terms of connections that are not there as much as the connections that are there. So you immediately have a view of the world in which, if you don’t have sparse connectivity, you can’t have Markov blankets. If you can’t have Markov blankets, you’re just left with a soup. There would be nothing in that kind of universe.

Imagine you lost your Markov blanket. That is basically what would occur at the point of death; you decay and dissipate. All the constituents of your body would no longer conform to this actively maintained boundary that you spend your entire life seeking evidence for and preserving for as long as you can. So the loss of your bounded integrity is simply a statement that you have lost the ability to maintain sparsity, to individuate yourself from the rest of the world. And when that happens, you dissolve, decay, dissipate, die, desiccate, all those D-words. They’re all statements of a loss of sparse coupling and the implicit loss of conditional independencies.

Returning to the brain, I’ve got friends who work in neuroanatomy, studying the connectome, and they like to say that the brain is empty. And what they mean is, if you draw a big adjacency matrix of the kind used in graph theory, and then fill in the entries of this matrix whenever there is a connection, then you find that out of all the possible connections that could be there, only a tiny fraction is actually present. And so when you first see this, it strikes you that the brain looks almost empty.

Of course, it’s that pattern of connectivity that defines a Markov blanket, and Markov blankets define the kinds of things that are coupled to each other. So what would happen if you failed to maintain that sparse coupling, failed to maintain your individuality, failed to maintain a distinction between you and everything else? What you’re talking about now is the destruction of this delicately structured, evolved set of contingencies, dynamics, and exchanges that keep you individuated.

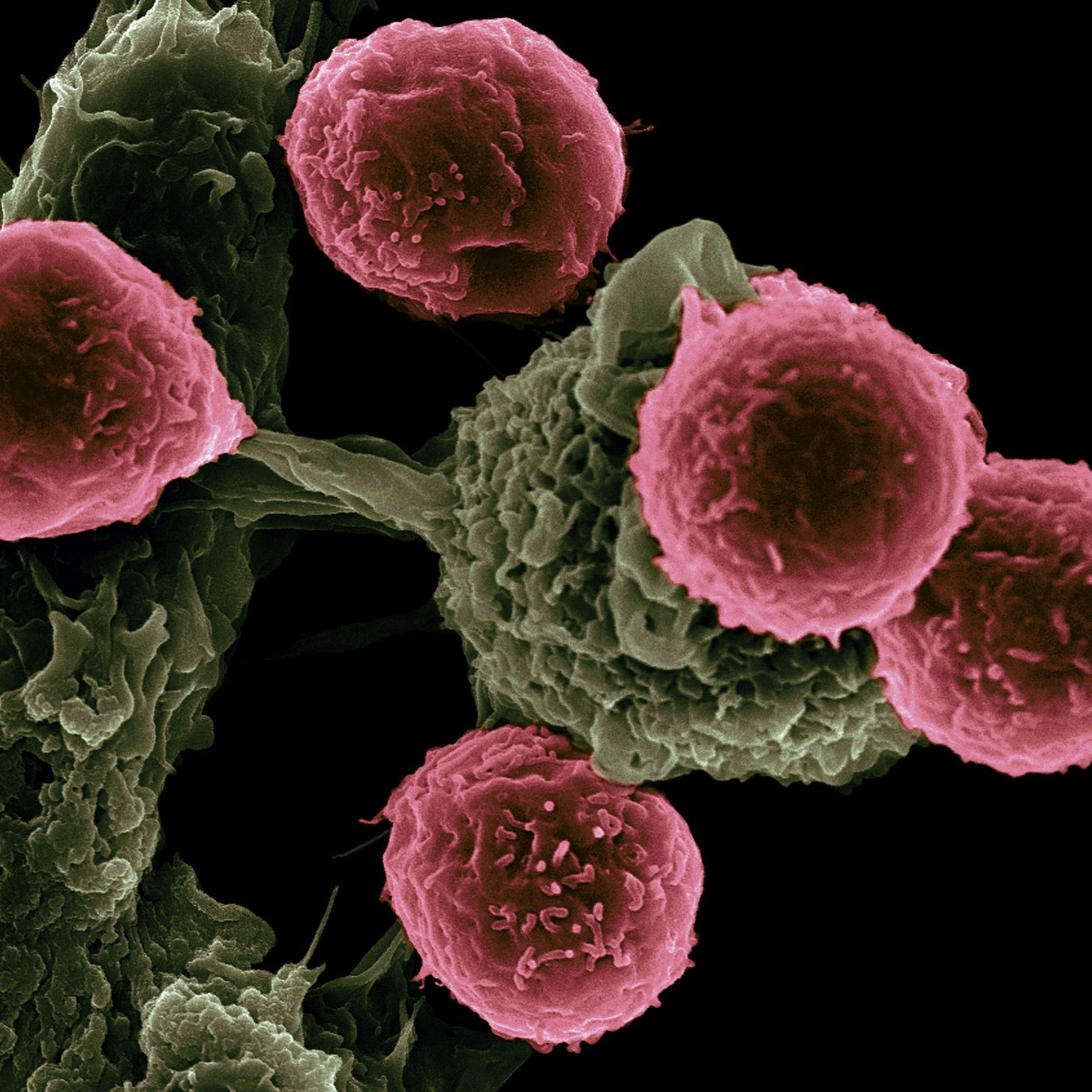

If you were a biologist and you wanted to find a metaphor for a failure to respect boundaries, basically destroying the sparsity that defines or is definitive of boundaries, then what you’re talking about is cancer. If you’re a politician, you’re talking about an invasion, you’re talking about Putin. If you’re a Big Tech person, you’re talking about disruptive technology and invasive technologies that break established economic structures. These kinds of disruptions, whether at a biological, societal, or geopolitical level, signify the destruction of the established connectivity and sparse dependencies. This is sometimes looked at as bad, sometimes good, depending on who you are and what kind of system is being disrupted. But I think the idea that dense connectivity through the disruptive technology of social media is a good thing is really a flavor of the last decade. I think the tables will turn, because the kind of dynamics which these technologies promote is exactly what you don’t want when you’re trying to minimize free energy. It’s not sustainable.

There is another way of looking at why you need that sparse connectivity. I’m going to go a bit technical now, but I can’t resist because I think this is a really important mathematical point, and it lends substance to the argument that if you go for globalization and over-connectivity in a Facebook sense, and don’t respect boundaries and sparsity, you will literally destroy the Earth. In order to maximize the likelihood of me finding you in an ecosystem at any point in evolution, you have to maximize your marginal likelihood of being there. More precisely, the marginal likelihood of all the exchanges with your environment, with your niche, with your friends on Facebook. That marginal likelihood is just another name for model evidence. So the model evidence is just the marginal likelihood. The log of the negative model evidence is bounded by the free energy.

The point here is that we have to maximize this evidence just to exist. You can look at this as adaptive fitness in theoretical evolutionary biology. And the log of evidence is equal to accuracy minus complexity, mathematically or statistically, which tells you immediately what you need. To be found in some kind of existence, i.e., maximize your marginal likelihood, you have to minimize your complexity. What does that mean? Well, it means minimizing the degrees of freedom that you are using to manage your exchange across your Markov blanket. What does that mean? Well, it means you have to carve nature at its joints in your head, or in your organization. You have to modularize. You have to factorize. Arguments predicated on globalization are, in some sense, based on a failure to do this properly.

Physicists have known this for centuries. It’s called a mean-field approximation, and it’s basically from this that you get thermodynamics. But from the point of view of this discussion, what that factorization or carving nature at its joints actually means is separating and disconnecting things so that you are leveraging the conditional independencies. Wherever you look, good systems—and by good, I simply mean those that have high adaptive fitness, or minimize their free energy, or maximize their evidence—will have a particular kind of sparsity. That sparsity almost invariably reminds us of the kind that underwrites an effective hierarchical organization, where you ensure that different parts of your organization are conditionally independent of each other. So basically, what I’m talking about is a kind of specialization. I’m talking about, if you’re an institution, recognizing that some people are good at doing this kind of thing and some people are good at doing that kind of thing, and they don’t need to talk to each other at their level. And that means that you can now introduce a sparsity in terms of message passing, and therefore the conditional influences between two departments. I don’t need to know how to be a good financier to do my job as a marketer, and vice versa. So, quite literally, carving nature at its joints in the way that we model the world beyond our Markov blanket is a sort of first principle account of why you’ve got so much sparse connectivity in any functional system that has the capacity to survive in a capricious or volatile environment.

GUNNAR: It is interesting that you use the analogy of cancer, because that’s a word that people sometimes use somewhat flippantly in political discussions when describing societal forces they believe are destructive. They’ll pin that word on a rogue institution or a group of rebels (who they might also label terrorists). And you mentioned globalization and climate change, which are also relevant, because some environmentalists describe humanity itself as a cancer that is eating away at the planet, which is really the “organism” that we are all a part of in a certain sense. I’ll put the morality of those kinds of statements aside for now, since I think they lead to the justification of some pretty ugly conclusions. But the motivation for using that kind of analogy appears to be, as you say, to point out that some part of a society or the planet is selfishly eating away at the rest in a way that will eventually collapse the system as a whole if it is not stopped.

A cancer cell is a cell that has become decoupled from the higher organizational structure of the organism, and so starts to act only to reproduce itself at the expense of the whole. It does this despite the fact that if it kills the organism, it obviously also kills itself. Michael Levin makes this point that cancer is what happens when one cell no longer recognizes itself as being part of that more holistic structure that is the organism. So we might see climate change as the inevitable consequence of humanity not recognizing itself as part of, and dependent for its survival on, the planet.

But then, what do we do now that we live in such a global society? I don’t see it as likely that we can return to the way things were in the past, I don’t even think we would necessarily want to. So how could a global society actually function well, without destroying the planet or turning into a “soup”?

KARL FRISTON: Again, it is really just about respecting the conditional independencies between your parts. In other words, you have to respect boundaries between groups, and you have to respect the privacy of individuals. And you see fluctuations in society when those boundaries are crossed. So in the 1980s, everybody wanted to be European, and then we had Brexit and other anti-EU rhetoric. There was a time when Scotland wanted to be part of the United Kingdom, but now it wants to be independent, etc. We see in history that there are always fluctuations and an attempt to establish and reshape boundaries and demarcations at every scale. The higher scale contextualizes the lower scale, but the higher inherits its structure from the lower. So they’ve all got to be compatible. Otherwise, you get counter-balancing forces, which is part of what we’re seeing now with this push towards deglobalization, which we may find disturbing on one level.

GUNNAR: So we can think of a lot of what is going on in society today as a kind of reaction against the “soupefying” and sparsity-breaking trends of the last half-century or so, like globalization, inequality, alienation from community, climate change, and so on?

KARL FRISTON: I think that’s right. And so to answer your previous question, what kind of structure would prevent us from dissolving into a soup or killing the planet? The answer is somewhat trivial. It is the structure we naturally tend to build around us. If you think from an individual perspective, you are naturally selective about how you create a well-chosen and maintained circle of friends, confidants, mentors, and mentees. So an interesting way to think about the Markov blanket is: If you and I talk to each other, but there is a third party that you talk to that I don’t talk to, then you become part of my Markov blanket with respect to that third party. Later, you might introduce me to this person, so that they become part of my Markov blanket with respect to the rest of the world, and so on. And this is a very adaptive way for systems to grow autopoetically.

But we can see why that is becoming more difficult. Our social transactions are now increasingly taking place on the web, and we are finding it very difficult to establish the right kind of sparsity in that ecosystem. I know it’s not vogue to say fake news, but you do run into issues of epistemic trust, because everyone ends up talking and listening to everyone without being able to differentiate the truthfulness or the relevance of the information. And the kind of dynamics you get there is very maladaptive. People become alienated, and society becomes very “soupefied”, as you said. So if society survives, that kind of thing will naturally incur a pushback, and you might get lots of regulation that will probably go too far, and then you’ll get people shouting about freedom of expression, which will also go too far in some way. But we will likely converge on some kind of happy medium where there is the right kind of scale-invariant partitioning and boundedness. That partitioning is necessary for you to get the kind of autopoetic effect where groups, societies, or the planet can survive and grow in an adaptive manner. But we could easily destroy that.

GUNNAR: I want to get a little deeper into what that looks like. You used the example of a business earlier; so you have these modularized parts, you have groups of marketers, financiers, product people, and so forth. Now, every business needs to have some level of communication between these; otherwise, you wouldn’t have a business. But you also have to avoid your organization turning into a soup by everyone talking to everyone all the time. I think the whole open-plan office trend from some years ago is an example of this. The idea was that everyone sits in one huge open space, and the departments are all mixed together, so everyone can easily just walk over and chat to each other whenever they please, and the hope was that this would make communication faster and that people would have more creative ideas. But this turned out to be a mess. People were far less productive because everyone was in each other’s business all the time, and there was no privacy either between departments or between individuals. So this soup-like structure actually reduced productive communication. Now, I assume the way you solve this problem in an organization has to do with scale? For instance, if you have the marketers and the product departments, rather than having them communicate directly with each other all the time, you have them both communicate to a “higher-scale” part of the business, which in turn looks at all the departments below.

KARL FRISTON: That’s it, that’s exactly right. So the answer is very simple. In my world, it’s just about having that deep structure. It’s just about building an adaptive hierarchy. And I repeat, in physics this is called a mean-field approximation, which is basically a factorization into conditionally independent latent states, or representations, or departments. However, you want to define what scale you’re talking about. So within any given scale, you have this modularity, where I’m reading one module as one factor. Just for your interest, this notion just falls directly out of the mathematical idea of a factor, like two times two equals four, where the two and the two are both factors of the four. If you can factorize a probability distribution into conditionally independent factors, then that’s a really powerful way of taking the pressure off the message passing. That would be, if you like, a computer scientist’s explanation for why sparsity is absolutely essential. It just minimizes complexity in terms of the computational cost of the message passing. That’s just another expression of what we were saying before. We have to minimize complexity to maximize evidence and marginal likelihood. So one of the great ways of doing that is to factorize within any given level. But you’ve also got that vertical factorization, which is the hierarchy.

So any successful institution one might envisage has to have a hierarchy. And, as you say, the way that these independent modules or factors within any one level become contextualized is by having a leadership team on top, and a leadership team on top of them, and a leadership team on top of them. And the way that they contextualize and cooperate is by sending messages up and down, and to some degree across, these levels. So if somebody is producing a brochure or a publicity release about a product and trying to predict how much revenue they will incur, then they need information. They need to get messages and constraints from the finance team and the product development team, etc. And exactly as you were intimating before, you are then looking for the right kind of integration. The preparation of the conditional independencies is done by vertical integration within a hierarchy.

By having a hierarchy, that’s another kind of sparsity. So notice the leadership team never speaks to the lorry drivers or the printers, because they don’t need to. That would be inefficient. That would be the soup. If they were chatting to the lorry driver, then everyone would get distracted by information that is not directly relevant to them. So this would be an example of the gross inefficiency of the soup organization. What we’re saying is that, by definition, this kind of over-connectivity, this kind of globalization of message passing and belief updating, is just not sustainable. It has to be sparse. If you’re an economist like Gerd Gigerenzer, you’d be talking about fast and frugal. This simply means that you’re passing messages or having transactions quickly and efficiently. And the frugality is absolutely important. It’s the sparsity, and the emergent Markov blankets that inherit from the sparsity, that equip self-organization with exactly that kind of efficiency or frugality.

GUNNAR: This loss of modularization sounds in some way akin to, in an informational or linguistic sense, the loss of nuance and context. To bring it back to the social media example, when we look at society and how people communicate and organize naturally, information is usually nuanced and contextualized by local constraints. So before social media, I would get my information about the world in a manner that was contextualized by the society, local community, and a group of confidants to which I belonged. But social media and the internet age more generally tend to take a lot of that contextualization and nuance away. There are, of course, some benefits to this, in terms of finding some good information you’d otherwise miss. Some issues really are global in nature, and the internet has been extremely valuable in that regard. But it seems that the more we replace local communication with globalized digital communication, the more our information exchange looks like a soup. It’s not just that you have everyone speaking in the same arena, it is that the arena itself obfuscates all the usual nuance that would allow you to contextualize the information you receive in a manner that makes it adaptive to you. And that seems to me to be part of the paradox of mass connectivity, because it simultaneously pulls everyone onto the same playing field and yet makes us feel more alienated than before.

KARL FRISTON: Yes, I mean, you could tell a story that is deeply worrying and pathological here. It’s a kind of invasiveness of our informational space. And another pathology that ensues from these soupefying dynamics is that everything becomes much more coarse-grained, which means that more and more of the system gets lumped into bigger and fewer chunks. In other words, you get a loss of nuance, as you were saying. We now have numerical studies suggesting that the only sustainable solution when you get this massive coarse-graining is basically a 50/50 split in terms of how parts identify in relation to the whole. Fifty or sixty years ago, say, you may have had a choice between at least eight or nine different flavors of political views. Now, you don’t. You’re either blue or red. And whatever “blue” or “red” means then becomes increasingly polarized. So from a mathematical perspective, this is just the consequence of when the system as a whole has been de-factorized into only one Markov blanket defining some binary partition. Whereas in a more sustainable, more evolved state of affairs, you would have a much more nuanced, fine-grained structure. So the dissolution of boundaries, namely the destruction of sparsity and conditional independencies, would be a natural way to look at polarization and entrenchment.

But the point being, it’s not so much that one is good or bad, it’s just a statement of the fact that you’ve become coarse-grained. And it’s really interesting to notice how this 50/50 split is becoming increasingly prevalent in political life. If you look at Brexit, it was 52% versus 48%. Biden versus Trump, Harris versus Trump, independence in Montreal or Scotland—it’s always about 50/50. I repeat, that’s the only evolutionarily stable strategy when you lack a fine-grained structure. If one group starts to get too small, then it’s going to be absorbed by the other group, and vice versa. You’re sitting on this unstable fixed point where there’s a very delicate balance. We wouldn’t have that problem if we had the opportunity to belong to one of eight in-groups, but we don’t. And that’s because of this over-connectivity, because of politicians engaging on X and Facebook and other globalization-style factors. We destroyed all that nuance and that delicate structure that took centuries or even millennia to evolve.

GUNNAR: It is so interesting that you say this, because growing up in Norway, one of the things that always struck me was how much less polarized we seemed compared to the US or the UK, where you always seemed to get this very strong left/right divide. Norway has always had a lot of parties, and at least six or seven parties that have had some genuine influence in parliament. I remember when I first had the right to vote, a group of people could be standing in a circle asking each other about who we were going to vote for, and each of us might say a different party, and yet no one would bat an eye or get angry at each other. But again, the strange effect of social media is that we seem to be increasingly importing the kind of polarized politics from those countries where the 50/50 split has taken hold. That doesn’t seem to have much to do with our political system or the local conditions; it seems to be very directly correlated with the degree to which our communication is becoming intertwined through the digital world.

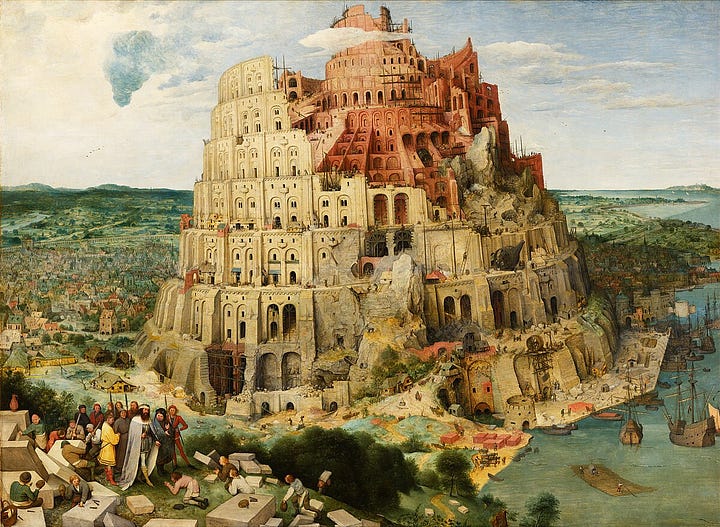

When you were speaking about this delicate balance around an unstable point, I had this image in my head that might be illustrative of this idea of sparsity versus coarse-grainedness. So imagine you have a pyramid, which is like a kind of hierarchy, with layers of stones stacked on top of each other. Now, a sparse pyramid would be propped up by many very small stones, so if one stone breaks or fails in some way, it is very unlikely that the whole structure will collapse. The other stones will be able to compensate for the weight, the broken stone can be quickly replaced, and the structure will survive. But then imagine a very coarse-grained pyramid, where the whole thing only consists of a few, large stones. If even one of those stones breaks, the whole thing is destabilized and the pyramid topples. Does that make sense?

KARL FRISTON: Absolutely yes, that’s basically what we’re talking about here.

Socio-Psychosis

GUNNAR: One thing I’ve always found interesting is how we quite naturally use psychological or biological language when we talk about societal structures and dynamics. Obviously, language is rife with allusions to one thing to describe another thing. So we talk about economic depressions, political organs, and the like. But I never took that to be more than an analogy, right? However, since learning more about the Free Energy Principle and how it is being applied to physics and biology, one interesting thing is that we’re finding a lot of conceptual exchanges across these disciplines. And so I wonder how some of the concepts from the FEP that you have applied to psychological functioning and pathology can be applied to societal issues.

KARL FRISTON: I’ll start, actually, with a biological example that Michael Levin likes to celebrate, which brings us back to cancer. So you can look at cancer as self-organization gone psychotic. You can look at a cancer cell as being so deluded that it does not respect the fact that the space occupied by its neighbors is not its space. This aspect is really just a failure to communicate. The cancer cell has the prior belief that “there is nobody next to me, and therefore I should occupy this space”. It’s not its fault, but it’s completely insensitive to the signals that are being generated by its neighboring cells. And this is a really important aspect of the kind of distributed cognition, or federated inference, that people like Michael Levin talk about in terms of the intracellular communication that allows cells to know their place. The title of the paper that we wrote together (“Knowing One’s Place”) is in reference to the fact that for self-organization to function, you need your individual Markov blanket parts to listen to all the signals coming from neighboring Markov blankets. That is what allows you to know your place in a way that is aligned with the rest of the structure that you are coexisting and co-constructing with.

So what that would suggest is that cancer is a pathology of inference. And this is, from a technical point of view, the same false inference that underwrites delusions and hallucinations in us humans. It rests upon a failure to listen to your sensations. You can read that as the failure to modulate prediction errors. For example, in a predictive coding scheme, it means you are not listening to the right prediction errors, either because you can’t attenuate them or you’ve lost the ability to modulate and ignore certain signals in the right way. And so you’ve compensated for this failure to attenuate your sensorium by making your own prior beliefs much more precise and much more rigid than before.

Now, how might we unpack that at a societal level? The current Israel/Gaza conflict is a horrific but illustrative example. What you’ve got here is a classic instance of sensory attenuation. So, in order for me to kill you, I have to ignore the evidence that I am killing something that does not deserve to be killed or that I am doing something that goes against my belief system. Therefore, you have to become an animal or an artifact, something inhuman like a pest, in order for me to kill you without damaging my sense of being a good citizen. My prior belief that I am the sort of thing that does not kill conspecifics or innocents is no longer violated. So if I am a member of the IDF, I have to attenuate or ignore any evidence that suggests that the people of Gaza are humans. And from the point of view of Hamas, they have to ignore the fact that Israelis are humans. This will happen at many different levels.

And this kind of thing is necessary to act under completely normal circumstances, right down to the level of saccadic suppression. Because of the way our eyes sample the world, I can’t see when I move my eyes, so my brain ignores the visual information while I’m moving them. And the way we compensate for that is we essentially sample the world whenever our eyes are still. I have to do the same kind of thing to move my limbs: in order to initiate a movement of my arm, I have to ignore the sensory information that is telling me that my arm is not moving. This mechanism is actually one of the things that goes wrong in Parkinson’s disease.

Returning to the societal level, you’ve also got sensory attenuation in terms of news blackouts. So the Israeli government does not want its citizens, and certainly not the world, to know exactly what’s going on in Gaza. And it has to be like that. It has to be like that because if they did know everything that was going on, then they would not be able to license their behavior conditioned upon their prior beliefs about the kind of people they are, which is to say human, compassionate, and other attributes they subscribe to. Just think of the words that people bring to the table under these circumstances. Palestinians say: “We are not animals!” Well, from the point of view of the Israelis—and this is often made explicit in their language—they are at the moment. So I think that’s a really horrific example of the mechanics of active inference playing out in a way that directly mirrors the fundamental role of sensory attenuation and selective attention in the sense-making of a brain. Exactly the same phenomena are playing out at a societal level.

GUNNAR: You’re absolutely right that this kind of dehumanization seems part and parcel of almost any occasion you might think of where one society or group commits large-scale acts of violence or theft towards another. The classic example people always bring up is Hitler, with how he reduced Jews to vermin (and inflated his own people to a “master race”), but the same thing is now being done to the Palestinians on a horrific scale. Writings by serial killers or mass murderers often read very much like the kind of language that representatives of a nation will use when they are committing atrocities. I’d even say that you find a similar phenomenon, in a less heinous form, with CEOs of companies that are introducing disruptive technologies, to use your previous example. If you listen to them, they often appear to selectively attenuate any evidence suggesting there are negative externalities in what they are building, and sometimes they subtly dehumanize the people who are harmed by them.

KARL FRISTON: I suspect that it’s not usually intentional, but the mechanics have to be in play. So they might not be saying to themselves, “Oh, we’ll intentionally withhold this information,” or “I’ll intentionally think of this person as an animal so that I can kill them.” From the Free Energy Principle point of view, what we are speaking about is just that people have to attenuate information at some level, consciously or unconsciously, to behave in a manner that goes against their beliefs about themselves. They have to suspend their attention, or selectively switch off that which would not normally be switched off. And what we’re switching off, basically, is the message passing across the Markov blanket, in order to transgress against some border, whether in terms of morally “crossing a line” or literally crossing borders to justify a land grab.

Stuck In A Rut

GUNNAR: Staying with the mental illness analogies, I found the paper you wrote with Robin Carhart-Harris about “canalization” really insightful. The idea, as I understand it, is that many psychopathologies share a universal mechanism where maladaptive prior beliefs become entrenched in your generative model. This is particularly obvious with something like depression, in that depressed people become convinced of some self-sabotaging belief, and that belief becomes so ingrained that the person cannot function and cannot escape the belief. And I suspect certain societal maladies, like an economic depression, also potentially carry some of the same conceptual mechanisms as how depression is expressed in the brain.

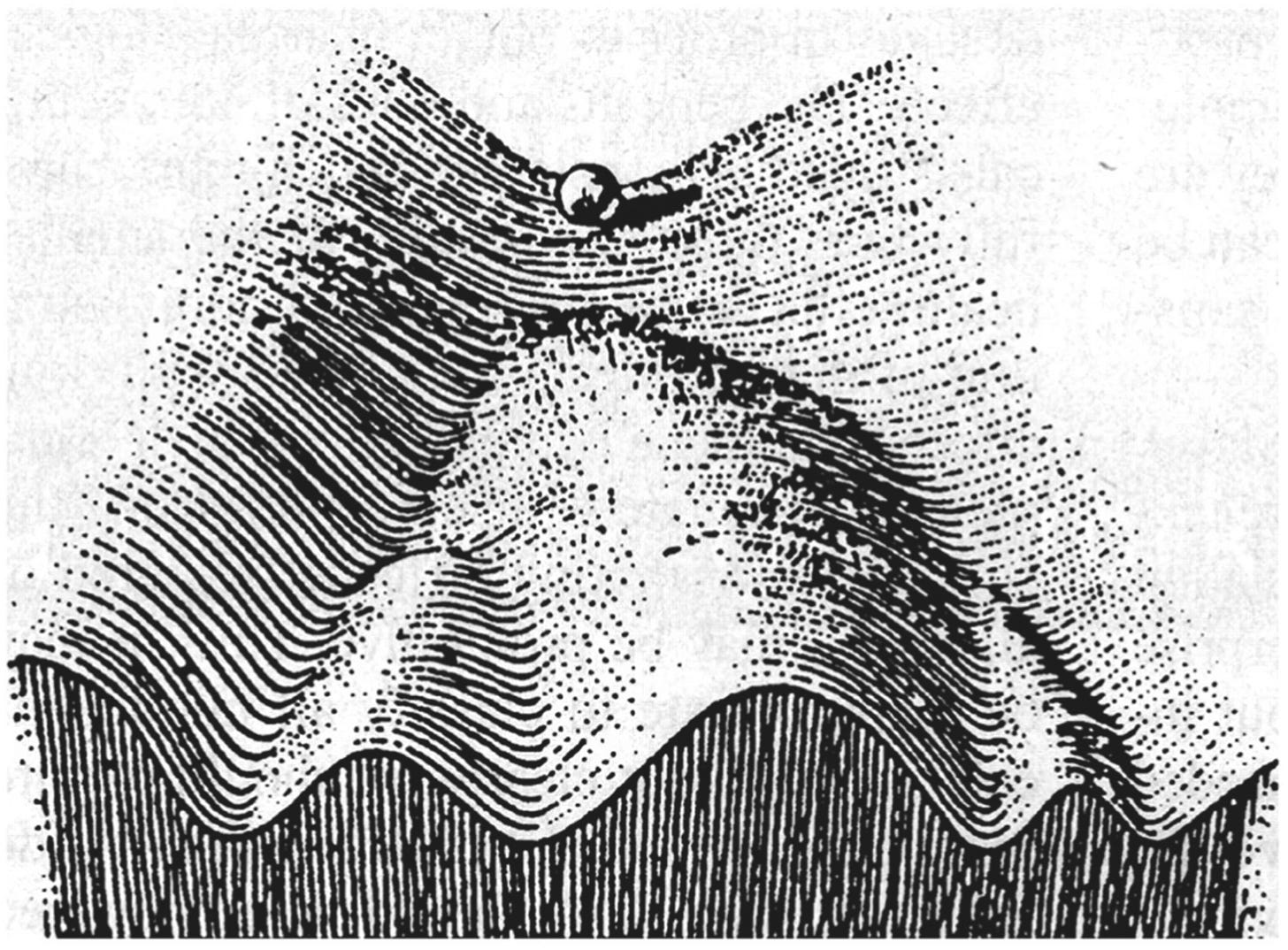

KARL FRISTON: In terms of active inference and the Free Energy Principle, many psychopathologies like depression share this common element of basically being “stuck in a rut”. It’s literally a rut that is defined by, in my world, a free energy landscape that is too precise. It’s like being trapped in a very sharp valley. The curvature means that there’s no wiggle room. So if you’ve got very, very precise prior beliefs, then you are effectively saying that you’ve got a very deep free energy minima from which you can’t escape. And certain ruts are self-sustaining. They’re not autopoetic, but they preclude getting out of the rut.

For example, if I am very depressed and I have a certain degree of agoraphobia, then I am never going to be able to go and gather the evidence that would contradict my belief that “I am not functioning outside my home”, or “I cannot function in social interactions with friends or family or strangers”. Such beliefs can be self-sustaining simply because they preclude the behavior—the active sensing and data gathering—that would challenge those beliefs. They prevent you from soliciting the kind of adaptive prediction errors that would force your generative model to update itself.

So that’s where effective treatments, like assisted psychotherapy or psycho-pharmacological interventions, attempt to broaden or flatten your prior precision so you can escape these minima. And, I repeat, this is not just the case for depression; it’s a common mechanism in things like obsessive-compulsive disorders, anxiety, phobias, and so on. These can often be understood as the same mechanisms but realized in different parts of your brain or your generative model of the world. That’s the main argument of the canalization paper Robin and others wrote. Canalization is just another way to express this idea of being stuck in a rut, or a deep free energy minima.

GUNNAR: What that makes me think of in terms of societal dynamics is, when you have an economic depression, often what happens historically is you’ll get the imposition of maladaptive austerity measures, which are meant to keep the economy from collapsing. But when austerity is handled poorly, it simply precludes the kind of economic activity that would allow society to escape from the depression.

KARL FRISTON: You can certainly argue for that kind of thing, that you’ve fallen into a societal state of mind where people believe there is no way out. And, of course, that means you can’t grow the economy to prove that there is, in fact, a way out.

GUNNAR: The other thing that came to mind is the kind of catastrophizing that comes from a more anxious mindset, where you experience a loss of confidence, and in trying to soothe your anxiety, you act rashly in a way that hurts you. So it’s a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy. And you see that kind of thing when, let’s say, the market has lost confidence, and people panic and dump all their shares and withhold their investments, and everyone does it all at once, so that the fallout is much worse than it otherwise would have been.

KARL FRISTON: That reintroduces this notion of uncertainty. And of course, uncertainty is just the complement of precision. If you don’t know what’s going to happen to you, in my world, that’s a reflection of beliefs with low precision. So the more uncertain you are, usually the more anxious you are. Interestingly, there can be comorbidity between anxiety and depression. They can exist at the same time along different dimensions. But sometimes, there’s a kind perverse pleasure in being depressed, because at least you believe you know what’s going to happen to you.

GUNNAR: Another thing Robin argues is that the way treatments like psychedelics work is by increasing brain plasticity and temporarily flattening your free energy landscape. So, basically, it’s like temporarily raising all those deep valleys so that you can escape them and form more adaptive ones. But on the flip side, psychedelics carry this risk of psychosis. Does that mean that depression and psychosis are opposites on the same spectrum?

KARL FRISTON: Technically, you can get depressive psychosis. I would say that a better conceptual axis is between psychosis and neurosis. So psychosis would be things like schizophrenia, and the neuroses would have their own axis of anxiety and depression, and the like. The mechanisms associated with psychosis are very much along the lines of a failure of sensory attenuation we were talking about, which then causes compensatory increases in prior precision. But this happens much more in the realm of sense-making and action, almost to the point where you could place something like Parkinson’s disease into this camp. In Parkinson’s, there’s something really broken about the link between what I see and how I move. Whereas neuroses like anxiety and depression are more cognitive and removed from sensory-motor integration and sense-making. They are more about interpersonal relationships, attributing intentional stances to other people, and beliefs about one’s past and future. So it’s more high-level, and less sensory and action-oriented.

GUNNAR: To dig a bit more into that, I’ve seen you use the word ‘cascade’ when describing the very delicate balance that the hierarchical structure of the brain has to manage in terms of keeping the whole structure stable, and why some precision is always necessary. So, without the right kind of precision along the levels of your generative model, you could end up in a situation where a slightly anomalous bit of information from your sensory states sets off a cascade that propagates up the hierarchy in a destructive way. Again, to use the analogy of a literal physical structure, you can imagine that if a building is not designed to absorb shocks and tremors, then you get this amplification, where a small tremor at the bottom of the structure propagates all the way up until the building collapses.

KARL FRISTON: That’s exactly right, and it can be quite devastating. To reaffirm, this is why we need some degree, or the right kind, of sensory attenuation. One of the devastating effects of failing to attenuate ascending prediction errors is that now a small or insignificant prediction error is in a position to revise your beliefs in a way that completely washes away all your prior intentions. For example, let’s just take Parkinson’s disease. Let’s say I have the intention to lift my mouse. Now, if I pay attention to the fact that before I move, my muscles are not moving, then the prediction errors generated will not be attenuated. Therefore, they will immediately revise my belief. So that unattenuated prediction error, particularly in the proprioceptive domain, trickles up the hierarchy and changes my mind; it completely dissolves my intention to move. So what would that look like? It would look like bradykinesia. It would look like a failure to initiate movement. It would look like I’ve lost volitional control simply because I can’t ignore the fact that I’m not moving. So you need to attenuate in order to act. And if I can’t do that, I’d basically be frozen; I’ll be catatonic.

GUNNAR: I wonder if this relates again to the kind of dysfunction we get from social media. I’m just thinking of how social media decontextualizes and strips the nuance from the flow of information in society. On X, for example, all this hyperbolic and conflicting information, whether from reliable or unreliable sources, is presented in this kind of flat way; all the posts look equally salient, which seems like it would make it difficult to attenuate information in the right way. Some bot or troll can post something that will cascade through the entire network and cause a great uproar. Politicians will respond to what is effectively just a few hyper-angry people as if it were the will of the whole society, or as if it were a political scandal that they need to compensate for. And you can witness in real time how public figures that spend a lot of time on these platforms, like Elon Musk, become increasingly polarized, extreme, and, frankly, bizarre in their rhetoric. Again, it is almost as if they are failing to attenuate information in a healthy way.

KARL FRISTON: That is an interesting example. I hadn’t thought of that before, but it fits perfectly. I personally have never met Musk, but I’ve met some of his earlier colleagues, and he appears to have certain autistic traits. The characteristic of a person with autism is that they struggle with sensory attenuation. So they are persistently glued to the sensorium, they like all the details, and they evince a kind of attention deficit disorder where they struggle to create deep central coherence. They cannot ignore all the minutiae of their sensory experience. So it makes perfect sense to me that this kind of unhealthy peripheral sense-making encouraged by social media would be particularly exacerbated in someone who struggles with attenuation.

Viva La Revolución

GUNNAR: There’s one final concept I’d love to ask you about, and I have no idea if it will make sense, but here goes. What is a “revolution” from a Free Energy Principle perspective?

KARL FRISTON: Oh, interesting. I’ve never been asked that question, so I don’t have an off-the-cuff answer. But immediately, what came to mind is what is implicit in the name. So we’re talking about something revolving. And in my world—well, in the world of physics and self-organization—that’s known as solenoidal or circular flow. And that’s the kind of dynamics you get when you stir a cup of coffee. But it is also characteristic of biotic self-organization, from the very fast oscillations in the brain through to biorhythms, breathing, respiration, and life cycles. At every temporal scale, you get this revolution.

It is a hallmark of any itinerant biological system, so anything living, that you have to revisit your attracting states from time to time. So when you ask me, “What is a revolution?” I immediately think of these biotic cycles and how that would be motivated by the teleology that is licensed by the Free Energy Principle. And the answer is that we’re usually talking about a kind of reset. Take the sleep-wake cycle: when we go to sleep, we basically do our house-clearing, which technically is the minimization of complexity or the removal of redundant connections in order to maintain the sparsity of our structure. And this fits beautifully with that sparsity notion. Sparsity is good, but you have to work hard to maintain the right kind of sparsity, and that’s probably why we go to sleep. Your free energy is creeping up as you go through the day until you really need some sleep to clear it out. So when we sleep, we actively regress or remove all those spurious associations, that over-connectivity, all that fake news that’s accumulated through the day. And then we feel nice and sparse and fresh for tomorrow, and off we go again.

So I imagine a societal revolution has the same function. It’s a house-clearing operation, where you get rid of redundant dependencies and structures that are overburdening. You can imagine going through 14 years of Tory rule—then you have to have a reset…

Speaking of resets, if you’ll excuse me, I really need a cigarette before I start a PhD examination.

For those who are interested, you can learn about the Free Energy Principle and its application to the mind, learning, and behavior from the book Active Inference published by MIT Press. Another accessible book about the kind of framework spoken about here is Andy Clark’s book The Experience Machine. You can get more intuitions about the kind of physics that comes out of the Free Energy Principle from my dialogue with the physicist Chris Fields.